The Schooner Result

This is the story of how this Victorian sailing ship came to be sitting on dry land at the Ulster Transport Museum in Cultra.

The Schooner Result was built in 1893 by renowned shipbuilder, Paul Rodgers.

During her 74-year working life Result became one of the best-known and most successful schooners in the coastal and home trades, noted for her speed, profitability and graceful design.

Result’s later adventures included serving in the First World War as a Q-ship, equipped with hidden armaments to attack U-boats.

She also starred in the 1951 Carol Reed film ‘Outcast of the Islands’. Result has been described as the ‘finest small sailing ship to have ever been built in these Isles’.

Leaving Exeter

Following a working career of 74 years, Result ceased trading in 1967, after it became increasingly difficult to find work.

Her Captain, Peter Welch decided to convert the hold into passenger accommodation for charter work, but he died before this could be completed.

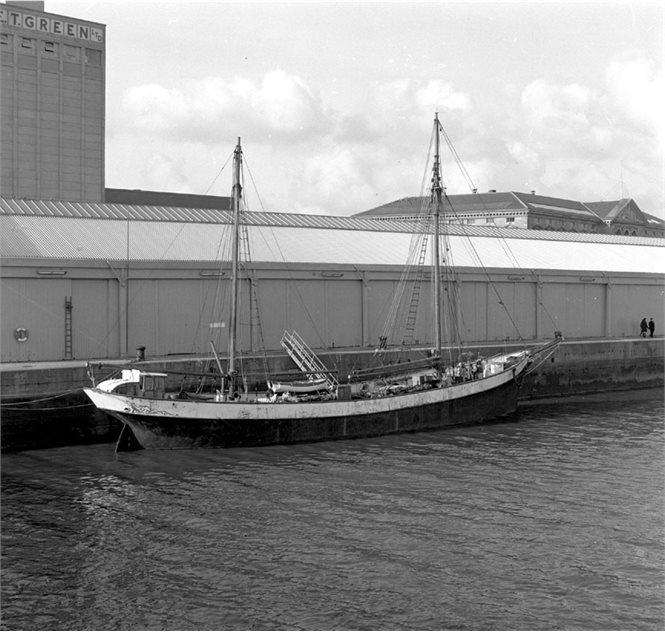

Result was moored in Exeter until she was bought by the Ulster Folk and Transport Museum in 1970 for preservation.

This photograph was taken during a visit by George Thompson, Director of the Ulster Folk and Transport Museum, and Michael McCaughan, Maritime Curator, to the Exeter Maritime Museum in July 1970. HOYFM.L1366.4

Arriving in Carrickfergus

Once the museum owned the Result, it put together a crew to sail her back to Northern Ireland.

She was commanded by Captain Tommy Jewell who had previously been Captain of another three-masted schooner; the Kathleen and May.

Result sailed into Carrickfergus, the town where she was built in 1893, on 26th October 1970. She was a week late due to storms in the Irish Sea forcing the ship to take shelter in Milford Haven.

Many members of the public, museum officials and local councillors gathered on the pier to welcome Result home.

Result in Belfast Lough on her final voyage back to Northern Ireland following her purchase by the museum in October 1970. This photograph was taken from a pilot boat. HOYFM.L458.2

From Carrickfergus to Belfast

The following day, in the pouring rain, Result set sail on her final sea voyage from Carrickfergus to Belfast.

On board were dignitaries from the museum and Carrickfergus council.

Upon arrival in Belfast she was moored at Donegal Quay. Due to her historic significance, Belfast Harbour Commissioners kindly provided Result with these berthing facilities for free.

Mr Wilgar: Night Watchman

Result stayed laid up alongside the quay at Queen’s Bridge while the museum gathered funds to restore her and move her to Cultra.

In the meantime, Mr William Wilgar was hired as watchman. In a newspaper interview in 1971 Mr Wilgar was described as a ‘jack-of-all trades’ who had worked as a London bus driver, quarry foreman and a pipe layer before getting the job on the Result. From his cabin in crew’s quarters in the bow it was his job to ensure that no unauthorised person got on board.

Despite claiming he didn’t get bothered much, Mr Wilgar had to, on a few occasions, chase away some people who wanted to come on board and walk around. He also encountered young people who threw stones at the ship from the bridge.

Mr Wilgar’s worst moment happened when he woke up in the middle of the night to find that someone had unhooked all the ropes and cast him adrift in the Lagan. In his newspaper interview he said: ‘Lucky for me I am a light sleeper and heard the person so I was able to jump on to the quay and tie up before the boat floated out’.

The watchman described life aboard Result as ‘cosy…even though it may be blowing and raining above, I am fine’. Even though he spent nearly 24 hours of each day on or about Result Mr Wilgar said he did not get lonely: ‘I have got to know a lot of the dockers who work here and I can chat with them and go to their canteen…I really enjoy living on board and will be sorry when I have to leave’.

Repairs at Harland & Wolff

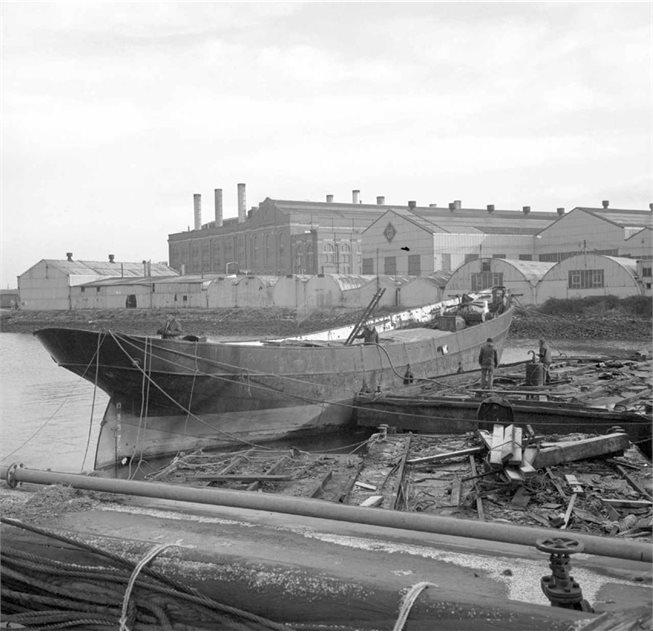

The museum hired Harland & Wolff to carry out a number of repairs and restoration work. For this work Result was brought into the Hamilton Dry Dock, which today houses the SS Nomadic.

In order to restore her back to her original 1893 specification later additions, such as her wheel house, engine and propeller, were removed.

In 1978 Result was brought back into Harland & Wolff, so that more repair work could be carried out and she could be prepared for her move to the Ulster Transport Museum.

In preparation for this move her masts, spars and rigging were removed at Thompsons Wharf – the same place where RMS Titanic was fitted out over 65 years earlier.

Constructing the cradle

Result was then placed in the Harland & Wolff building dock for more restoration work such as filling in the propeller aperture and bringing the hatches back to their original size.

For the move to Cultra the shipyard was tasked with constructing a cradle for the ship to sit on.

This cradle still holds the ship today.

Samson lifting the Result

Once the cradle was finished Result was lifted out of the building dock by Harland & Wolff crane Samson and onto the cradle.

Ready for the journey to Cultra

A self-jacking trailer was placed under the cradle and ship. The trailer was then jacked up so Result could be taken by road to the Ulster Transport Museum.

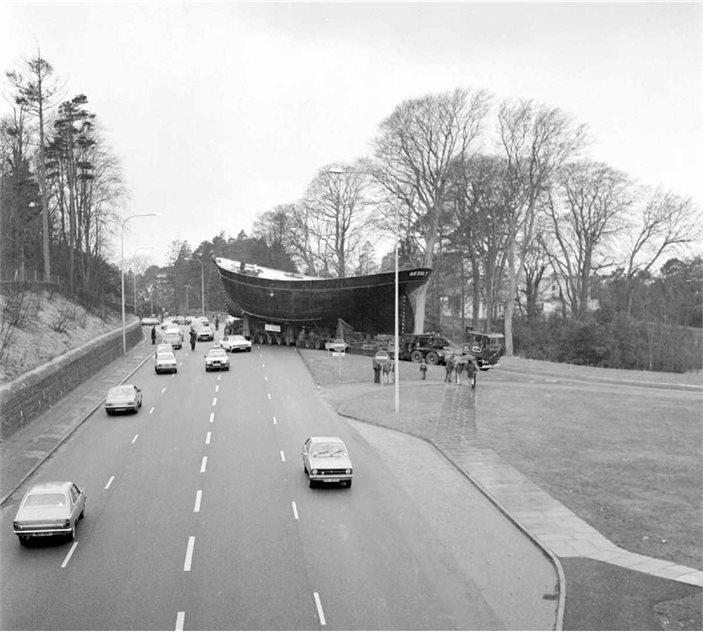

On the road to Cultra

Despite the museum only being 8 miles away from Harland & Wolff, the move took 10 hours as Result slowly moved along the streets.

Road users must have been bemused at the sight of a 122-ton Victorian ship passing by them. Perhaps they took it as an elaborate April Fools’ Day joke as the move took place on Sunday 1st April 1979.

Arriving at the museum - the end of the voyage

The move into the museum’s grounds produced some extremely surreal scenes as the Victorian sailing ship passed over the railway bridge and moved along amongst the trees.

In order to take the weight of the ship the bridge was strengthened in preparation for the move.

At the end of her voyage by road Result was placed next to the Dalchoolin galleries at the Transport Museum.

Her last voyage, albeit one extremely different to other ships and one that the men who built her in 1893 could have never imagined, was over.

Result remains there to this day, displayed without her masts and rigging, for the public to see this remarkable survivor from the Victorian age of shipbuilding and the First World War.

Guest blog by Christopher Kenny